DON EDDY

IN THE NEWS

Artist Statement

Don Eddy

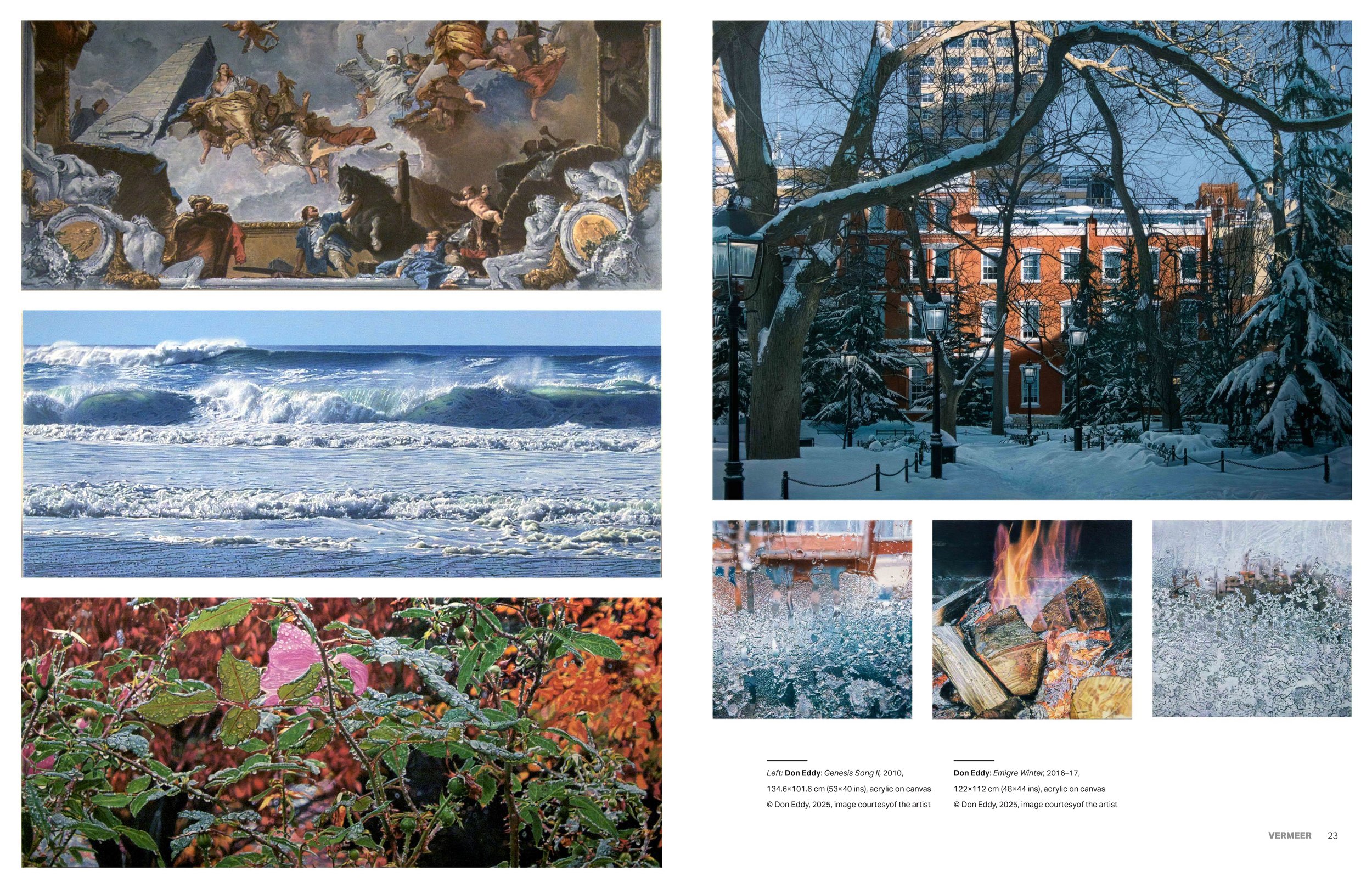

From 1990, a distinguishing feature of my work has been the format of the work itself. A single painting is made up of two or more panels. There are diptychs, triptychs, and even polyptychs. Freely derived from Medieval altarpieces, the whole is a product of several images. When introduced, this work was greeted with a mixture of puzzlement and resistance. Over time, I sensed a grudging acceptance of the format even though it was not fully understood. But the questions persisted: Why was it necessary? What function did it perform? and What did itmean? Though unusual in contemporary representational art, there is much to recommend a multi-paneled format. I could write a small book on the many advantages of deploying this format, but I will limit myself to a discussion of one issue: the tensions between perception and experience. To address this issue I will introduce you to the “problem of the corn plant.”

On Easter Sunday, maybe 35 years ago, I was given the gift of a tiny house plant, commonly known as a corn plant. A simple present of no particular interest to me, I probably accepted it with poorly disguised contempt. Over time, though, I developed a fondness for the plant and took care to nurture it. In due course it grew from a wee thing into something approaching a small tree (about 190cm). Today, having traveled with it from place to place it sits majestically in my front window.

If you were to visit me, sooner or later, it would likely attract your attention. What you would see would not seem all that special, just a fairly large house plant that is clearly thriving. I, on the other hand, would see 35 years of my life. Standing in front of that humble plant I would see my daughter, growing from a small child to a successful adult. I would see a marriage dissolve, and, in time, a new and permanent love take its place. I would see the winding road of a career in art, the ups and downs, the slow maturation of the work. Simply put, you would perceive the plant. I would experience, in that plant, the flow of my life. But not really. Even you, with no prior experience of this particular plant, would not so much ”see” the plant as experience it through the veil of your hopes, preferences, prejudices, and history.

“The problem of the corn plant” is: How does one deal with the richness of experience as it is embodied in simple “things”? And how does one communicate that in the context of art? This creates a special difficultly for representational art. It illuminates a substantial weakness when depicting “things” on a single paneled work of art. If I were to, let’s say, paint that corn plant, how would I imbue it with the depth and richness of my experience? I would contend that it cannot be done in the context of a single paneled representational painting. You can affect mood, emotion, and psychology, but not experience. You could attempt to deal with the problem by including many images on a single panel, but that inevitably invokes the burdensome specter of Surrealism with its attendant psychological issues.

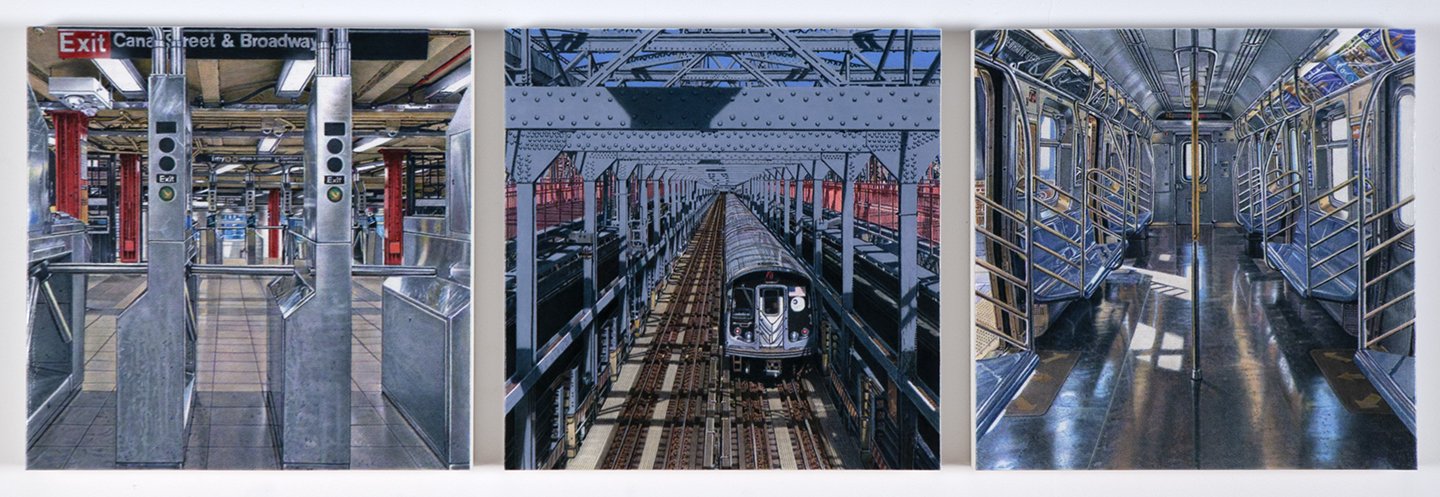

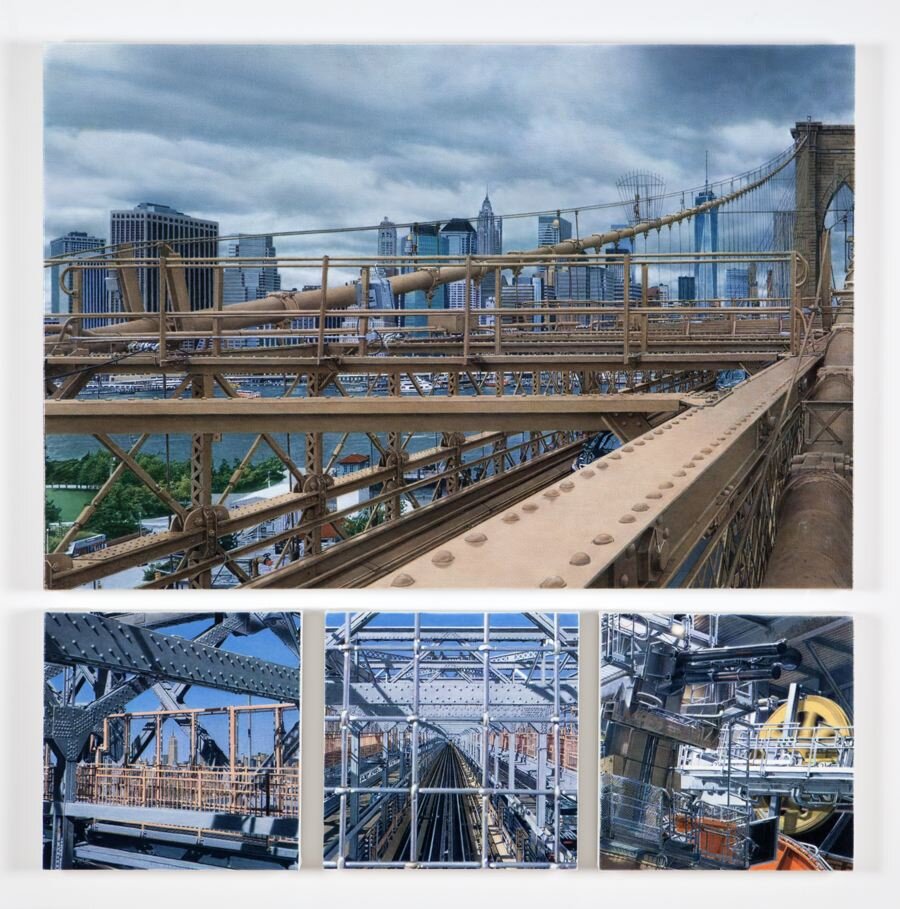

After years of struggle and resistance, it occurred to me that the solution was to adopt the format of multi-paneled paintings. The inevitable subject of a multi-paneled paintings is not “things” but “relationships.” In such a work, a conversation is generated among images that is more like our experience than our perception. It is not necessarily a didactic conversation with a preconceived meaning. Rather, meaning is generated in the context of a dynamic encounter among the multiple images and observer. Existentially, no meaning preexists the dialogue. As in our life, meaning is generated, in time, and in active encounters with people, places, and things. Our personal narratives, our personal histories are our narratives and histories only in retrospect. In the present, we have dynamic encounters in time that generate our experience and meaning. That is what my work hopes to do.

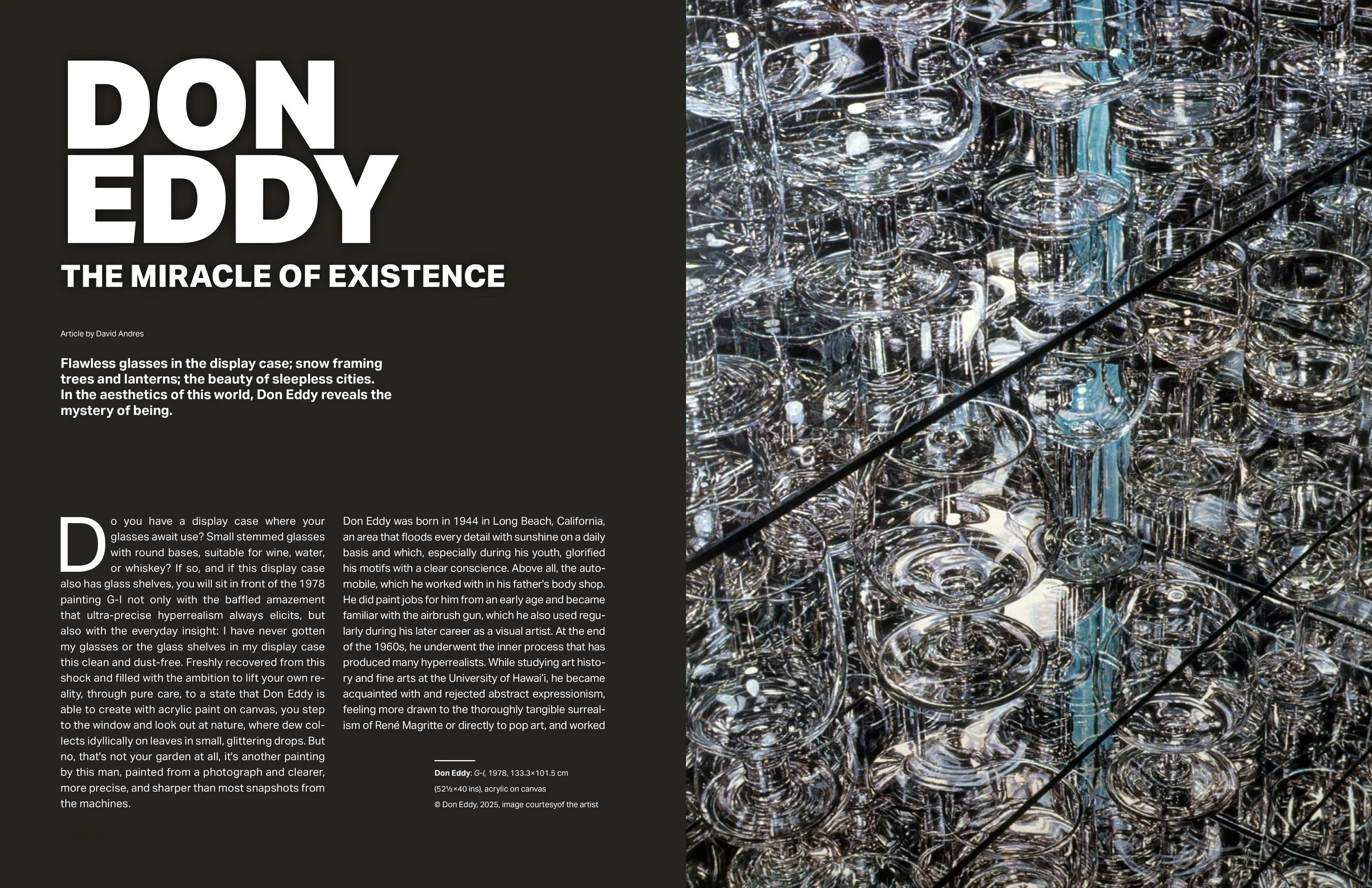

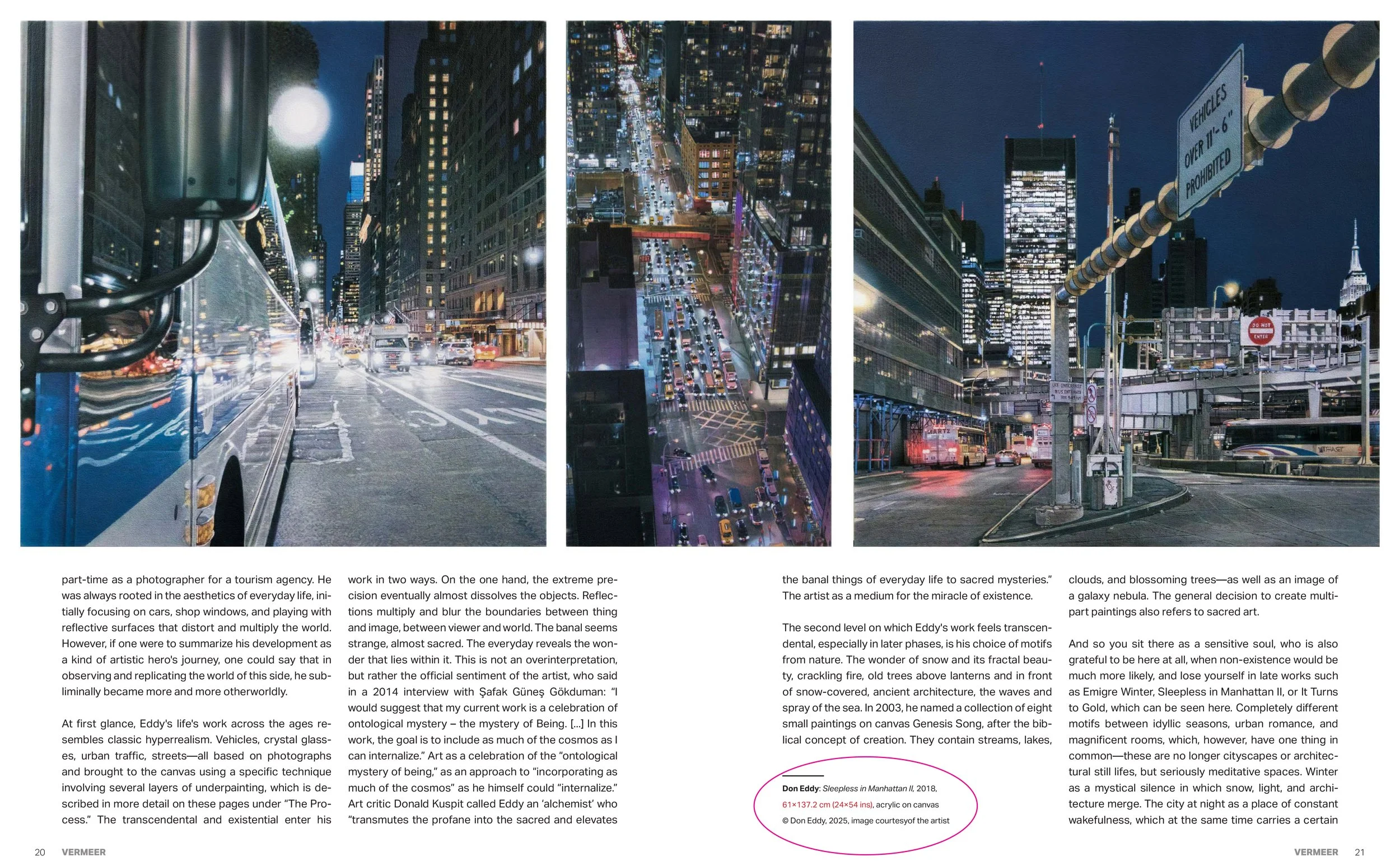

HISTORY AND TECHNIQUE

While Eddy’s earlier works of the ‘80s were object oriented, depicting glassware, silverware and toys on reflective glass shelves, his new paintings (and work of the past decade) have turned outward—to the imagery we behold in the world—as well as inward in their impact. No longer does the artist select images for cerebral, narrative or metaphorical reasons, he juxtaposes images that work in poetic relationship to one another. Eddy calls these connections of structure “echoing ecosystems” which anchor and join the panels together.

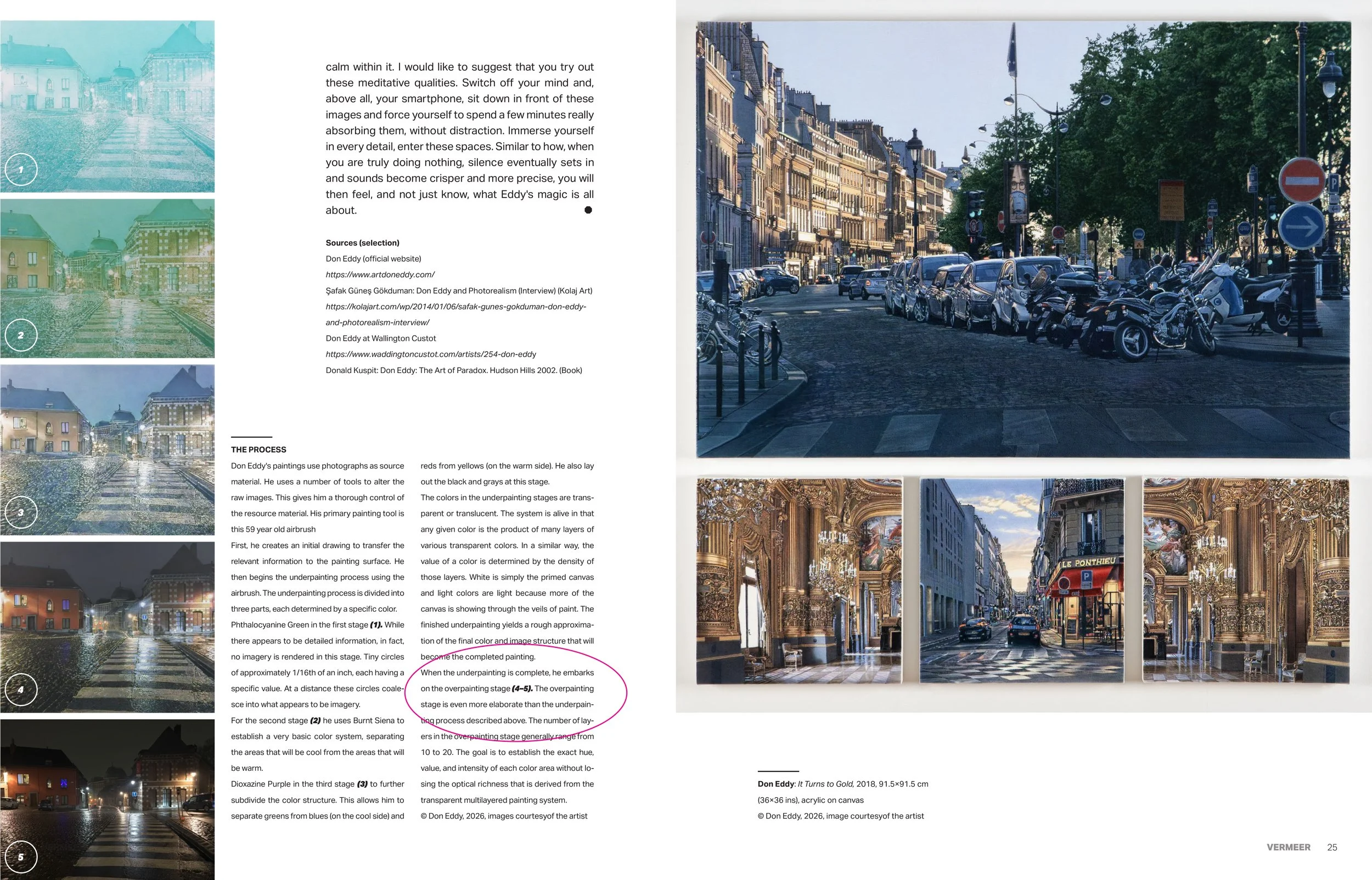

Eddy utilizes a unique system he has developed over the years, underpainting in three colors. The first layer is a phthalocyanine green in a series of tiny circles about 1/16th of an inch in diameter. Eddy meticulously paints each of the eight panels first in tiny green circles, a meditative process of setting the values for the painting. This layer is followed by brown, then purple to separate the warm from the cool colors.

He may then add between 20 to 30 layers of transparent color to achieve the radiant final palette of each painting. Eddy does not project a slide when creating his works; he draws a map onto the canvas that only he can read, and then begins to create a universe for the public to contemplate in its richness, quietness and depth.